2030 Moore tornado: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

== Development and track == | == Development and track == | ||

=== Formation and initial intensification === | |||

The tornado first touched down at approximately 1:21 p.m. CDT near Newcastle, Oklahoma, in an open rural field just southwest of State Highway 76. Initial damage surveys identified light EF0 tree damage and minor roof damage to an isolated outbuilding. Within moments, the tornado began to intensify, carving through open farmland where ground scouring was documented. In one location just west of Moore, topsoil was stripped away to a depth of several inches, and a small metal equipment shed was completely destroyed and scattered downwind, with debris found embedded in the ground. Surveyors noted this as the first instance of EF4-intensity damage, despite a lack of built structures nearby. | |||

Radar data indicated the parent supercell was rapidly evolving, with a tightening velocity couplet and a debris signature emerging less than five minutes after touchdown. The storm was embedded within a high-shear, high-instability environment that allowed for rapid intensification and tightening of the tornado’s circulation. Observers and storm chasers in the area reported a dramatic increase in condensation funnel size and rotational speed as the tornado approached the outskirts of the Oklahoma City metro. Its early transition from a weak rope to a wedge shape was noted within just ten minutes, signaling the beginning of what would become a deadly and historic event. | |||

=== South Oklahoma City === | === South Oklahoma City === | ||

As the tornado | As the tornado approached the Oklahoma City/Moore city limits, it entered a phase of rapid intensification and significant widening. The National Weather Service noted that this stretch of the tornado’s life cycle marked a distinct escalation in both damage potential and structural destruction. Wind velocity estimates from dual-polarization radar began exceeding 175 mph in this area. Numerous hardwood trees were completely debarked, and light poles were snapped or twisted near their bases. A cluster of manufactured homes and barns along the city fringe were reduced to piles of rubble and unrecognizable debris. | ||

The tornado’s path widened considerably, reaching nearly three-quarters of a mile as it moved along South Western Avenue. The damage in this zone was rated as high-end EF3 to low-end EF4. Homes constructed to pre-2013 standards were leveled, while others sustained partial wall collapse and total roof loss. Power lines were downed across major intersections, complicating emergency access routes. Despite early warnings, some residents were caught off-guard by the tornado's sudden expansion and forward acceleration. Multiple storm chasers and local meteorologists noted the “bowl-shaped” structure and inflow jets feeding into the tornado at this stage, consistent with strengthening. | |||

=== Moore === | === Moore === | ||

Upon | Upon entering south-central Moore, the tornado became a full-blown wedge nearly a mile wide and producing continuous EF4+ damage along its path. Winds exceeded 200 mph in several locations, with some residential subdivisions showing homes that were not only leveled but swept completely off their foundations. Video footage captured entire neighborhoods disappearing into the storm’s core. The tornado passed over Plaza Towers Elementary School, which had been rebuilt after its destruction in 2013. Though the school sustained substantial exterior and roof damage, its reinforced design prevented structural collapse. Fortunately, the school was unoccupied due to it being a Saturday. | ||

The tornado continued through central Moore with catastrophic consequences. Businesses along 4th Street were obliterated, and vehicles were hurled hundreds of feet—some found wrapped around trees or crushed beyond recognition. The peak damage occurred at a well-constructed, fully bolted-down restaurant in southern Moore. The building was completely destroyed, and anchoring bolts were found sheared or warped. Engineers determined that the structural failure aligned with EF5-level wind speeds, leading the National Weather Service to assign an official EF5 rating based solely on this damage indicator. Elsewhere, the tornado inflicted widespread EF4 destruction, particularly in areas along Santa Fe Avenue and Shields Boulevard. | |||

=== Weakening and dissipation === | === Weakening and dissipation === | ||

After | After exiting the most densely developed areas of Moore, the tornado began a gradual weakening trend. The debris ball on radar shrank in intensity, and Doppler velocity signatures diminished. As it approached the eastern edge of Moore and neared Lake Stanley Draper, the tornado narrowed and exhibited signs of occlusion. Damage surveys in this region documented EF2–EF3 damage to large outbuildings, scattered homes, and wooded areas. Several barns were flattened, and trees were snapped or stripped of limbs, but the consistent total destruction seen earlier had diminished. | ||

The tornado officially lifted at 2:07 p.m. CDT after being on the ground for 46 minutes. Its total path length was calculated at 15.1 miles, with a maximum width of approximately 1 mile at its peak. Despite its weakening, the storm remained powerful until the very end, with its final moments still producing damage consistent with EF2 intensity. In the hours following its dissipation, the National Weather Service began immediate aerial and ground surveys due to the extraordinary scale of destruction observed from both radar and eyewitness reports. | |||

== Impact == | == Impact == | ||

Revision as of 07:21, 30 April 2025

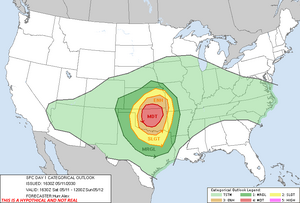

Bottom: Radar loop of the tornado as it went through Moore. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | May 11, 2030, 1:21 p.m. CDT (UTC-5:00) |

| Dissipated | May 11, 2030, 2:07 p.m. CDT (UTC-5:00) |

| Duration | 46 minutes |

| EF5 tornado | |

| on the Enhanced Fujita scale | |

| Path length | 15.1 miles (24.3 km) |

| Highest winds | 205 mph (330 km/h) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 35+ |

| Injuries | 315+ |

| Damage | ~$2.1 billion (2030 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cleveland and Oklahoma Counties in Oklahoma, mainly the city of Moore |

|

| |

| Part of the Tornado outbreak of May 11-12, 2030 and Tornadoes of 2030 | |

The 2030 Moore tornado was a catastrophic and violent EF5 tornado that struck the city of Moore, Oklahoma on May 11, 2030. As part of a tornado outbreak affecting the Southern Plains, this tornado caused widespread devastation across Cleveland and Oklahoma counties, leaving a trail of destruction reminiscent of the deadly tornadoes that struck the region in 1999 and 2013. The tornado reached a peak intensity of EF5 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, with estimated winds of 205 mph (330 km/h), and carved a destructive path through densely populated areas, making it one of the most intense tornadoes to impact the United States in recent history. The storm produced a mile-wide swath of obliteration that overwhelmed emergency response efforts, destroyed key infrastructure, and forced a massive regional mobilization.

Rated as the highest possible intensity on the Enhanced Fujita scale, the tornado was fueled by a volatile mix of extreme instability, strong vertical wind shear, and a potent mid-latitude cyclone that created near-perfect conditions for tornadic development. Its rapid intensification and close proximity to a major population center amplified its impact, catching many residents off guard despite early warnings. Video footage and radar analysis showed an exceptionally strong debris signature extending tens of thousands of feet into the atmosphere, further confirming the tornado’s strength. In addition to its wind speeds, the tornado’s longevity and relatively slow forward motion compounded the destruction, with some areas being raked by intense winds for several minutes.

This was the third EF5 tornado to strike the city of Moore, following the devastating events of May 3, 1999, and May 20, 2013. It also marked the third EF5 tornado to occur in the United States since 2013, breaking a nearly two-decade lull in top-rated tornadoes. Despite the widespread damage throughout the city, the National Weather Service assigned the EF5 rating based on a single damage indicator: the complete destruction of a well-constructed restaurant in southern Moore. The rest of the tornado’s damage, while extreme and consistent with EF4 intensity, did not meet the required damage indicators for an EF5 rating. However, the destruction of the restaurant, which had been bolted to its foundation and engineered to high standards, supported winds well over 200 mph. Engineers who reviewed the damage determined that the structural failure was consistent with total aerodynamic loading typically associated with EF5 wind speeds, making the classification a rare but justified decision.

The tornado initially formed west of Moore in rural areas near Newcastle, Oklahoma. After producing sporadic damage in open farmland, it rapidly intensified and grew in width as it approached the densely populated suburbs of Moore. As it moved into south-central Moore, the tornado reached its peak strength, producing catastrophic EF5 damage. The path of destruction extended for 15.1 miles, affecting thousands of structures and claiming dozens of lives before dissipating near Lake Stanley Draper after being on the ground for 46 minutes. The event served as a grim reminder of the region’s vulnerability to high-end tornadoes and reinforced Moore’s tragic legacy as a focal point of repeated tornadic devastation. In the aftermath, survivors and meteorologists alike drew chilling comparisons to previous Moore disasters, solidifying the 2030 tornado’s place in meteorological history.

Meteorological synopsis

On May 11, 2030, an intense mid- to upper-level trough emerged into the Southern Plains from the Desert Southwest, providing deep-layer ascent across Oklahoma and northern Texas. A strong 500 mb jet max of 90–100 knots overspread the region, resulting in significant upper-level divergence. At the surface, a rapidly deepening low-pressure system centered near the eastern Texas Panhandle helped draw a warm front northward across central Oklahoma. This frontal boundary intersected a sharpening dryline stretching from southwestern Oklahoma into western Kansas, forming a textbook triple point scenario.

The environment featured extreme instability, with surface temperatures reaching 86 °F and dewpoints around 73 °F. Surface-based CAPE exceeded 4450 J/kg, and 3-km CAPE also showed non-negligible values around 123 J/kg, indicative of buoyant air even in the lower troposphere. Steep lapse rates were observed throughout the depth of the troposphere, with 0–3 km lapse rates reaching 8.7 C/km and 3–6 km lapse rates at 7.4 C/km, supporting rapid vertical acceleration of parcels. Storm-relative helicity values were measured at 457 m²/s², suggesting a high potential for low-level mesocyclones and tornado formation. The 700–500 mb relative humidity measured 55%, showing moderate mid-level moisture, while precipitable water values were modest at 0.4 inches — a signal that while deep moisture was somewhat limited, the boundary layer was extremely favorable for classic tornadic supercells.

Surface relative humidity near 83% added to the explosive instability profile, enhancing downdraft and outflow boundaries that later reinforced tornadic mesocyclones. These conditions were coupled with strong vertical shear from the surface to mid-levels, with deep-layer shear likely exceeding 50 knots in portions of central Oklahoma. Wind profiles revealed strongly veering winds with height — southeasterlies at the surface transitioning to southwesterlies aloft — producing long, looped hodographs consistent with cyclic tornadic storms.

Surface analysis and mesoscale observations confirmed strong moisture convergence near the triple point, where initial supercells rapidly formed. Satellite imagery and rapid-scan radar confirmed explosive convective development by early afternoon, with initial towers quickly exhibiting overshooting tops and strong mid-level rotation. Additional support from a diffluent upper flow pattern and deep-layer shear allowed for rapid supercell organization, particularly near the I-35 corridor. Hodographs taken from Norman and other central Oklahoma soundings displayed large, clockwise-curved profiles in the lowest 3 km, indicative of enhanced tornado potential.

The Storm Prediction Center issued a Moderate Risk for severe weather with a focused threat for strong to violent tornadoes. A Particularly Dangerous Situation (PDS) tornado watch was issued by early afternoon, emphasizing the potential for EF3+ tornadoes with long tracks. Environmental soundings taken from central Oklahoma showed a large, curved hodograph, indicating strong directional shear and long hodograph loops ideal for cyclic tornadogenesis. Surface winds backed across central Oklahoma, further enhancing low-level shear. By early afternoon, discrete supercells began forming in the triple point region, with one storm rapidly intensifying southwest of Moore and producing the tornado that would become the day's most destructive. in the triple point region, with one storm rapidly intensifying southwest of Moore and producing the tornado that would become the day's most destructive.

Development and track

Formation and initial intensification

The tornado first touched down at approximately 1:21 p.m. CDT near Newcastle, Oklahoma, in an open rural field just southwest of State Highway 76. Initial damage surveys identified light EF0 tree damage and minor roof damage to an isolated outbuilding. Within moments, the tornado began to intensify, carving through open farmland where ground scouring was documented. In one location just west of Moore, topsoil was stripped away to a depth of several inches, and a small metal equipment shed was completely destroyed and scattered downwind, with debris found embedded in the ground. Surveyors noted this as the first instance of EF4-intensity damage, despite a lack of built structures nearby.

Radar data indicated the parent supercell was rapidly evolving, with a tightening velocity couplet and a debris signature emerging less than five minutes after touchdown. The storm was embedded within a high-shear, high-instability environment that allowed for rapid intensification and tightening of the tornado’s circulation. Observers and storm chasers in the area reported a dramatic increase in condensation funnel size and rotational speed as the tornado approached the outskirts of the Oklahoma City metro. Its early transition from a weak rope to a wedge shape was noted within just ten minutes, signaling the beginning of what would become a deadly and historic event.

South Oklahoma City

As the tornado approached the Oklahoma City/Moore city limits, it entered a phase of rapid intensification and significant widening. The National Weather Service noted that this stretch of the tornado’s life cycle marked a distinct escalation in both damage potential and structural destruction. Wind velocity estimates from dual-polarization radar began exceeding 175 mph in this area. Numerous hardwood trees were completely debarked, and light poles were snapped or twisted near their bases. A cluster of manufactured homes and barns along the city fringe were reduced to piles of rubble and unrecognizable debris.

The tornado’s path widened considerably, reaching nearly three-quarters of a mile as it moved along South Western Avenue. The damage in this zone was rated as high-end EF3 to low-end EF4. Homes constructed to pre-2013 standards were leveled, while others sustained partial wall collapse and total roof loss. Power lines were downed across major intersections, complicating emergency access routes. Despite early warnings, some residents were caught off-guard by the tornado's sudden expansion and forward acceleration. Multiple storm chasers and local meteorologists noted the “bowl-shaped” structure and inflow jets feeding into the tornado at this stage, consistent with strengthening.

Moore

Upon entering south-central Moore, the tornado became a full-blown wedge nearly a mile wide and producing continuous EF4+ damage along its path. Winds exceeded 200 mph in several locations, with some residential subdivisions showing homes that were not only leveled but swept completely off their foundations. Video footage captured entire neighborhoods disappearing into the storm’s core. The tornado passed over Plaza Towers Elementary School, which had been rebuilt after its destruction in 2013. Though the school sustained substantial exterior and roof damage, its reinforced design prevented structural collapse. Fortunately, the school was unoccupied due to it being a Saturday.

The tornado continued through central Moore with catastrophic consequences. Businesses along 4th Street were obliterated, and vehicles were hurled hundreds of feet—some found wrapped around trees or crushed beyond recognition. The peak damage occurred at a well-constructed, fully bolted-down restaurant in southern Moore. The building was completely destroyed, and anchoring bolts were found sheared or warped. Engineers determined that the structural failure aligned with EF5-level wind speeds, leading the National Weather Service to assign an official EF5 rating based solely on this damage indicator. Elsewhere, the tornado inflicted widespread EF4 destruction, particularly in areas along Santa Fe Avenue and Shields Boulevard.

Weakening and dissipation

After exiting the most densely developed areas of Moore, the tornado began a gradual weakening trend. The debris ball on radar shrank in intensity, and Doppler velocity signatures diminished. As it approached the eastern edge of Moore and neared Lake Stanley Draper, the tornado narrowed and exhibited signs of occlusion. Damage surveys in this region documented EF2–EF3 damage to large outbuildings, scattered homes, and wooded areas. Several barns were flattened, and trees were snapped or stripped of limbs, but the consistent total destruction seen earlier had diminished.

The tornado officially lifted at 2:07 p.m. CDT after being on the ground for 46 minutes. Its total path length was calculated at 15.1 miles, with a maximum width of approximately 1 mile at its peak. Despite its weakening, the storm remained powerful until the very end, with its final moments still producing damage consistent with EF2 intensity. In the hours following its dissipation, the National Weather Service began immediate aerial and ground surveys due to the extraordinary scale of destruction observed from both radar and eyewitness reports.

Impact

Damages

Over 2,000 structures were damaged or destroyed, including homes, schools, farms, and commercial businesses. Entire blocks of neighborhoods were reduced to rubble. The hardest hit areas included neighborhoods along 4th Street and Santa Fe Avenue, where nearly every structure was flattened. Critical infrastructure including water treatment facilities and cell towers were impacted, hampering response and communication in the hours following the storm.

Briarwood Elementary School

Briarwood Elementary sustained roof and wall damage, with several classrooms severely impacted. Fortunately, like Plaza Towers, it was closed for the weekend. The structure was found to have partially failed due to uplift, despite code improvements made after the 2013 tornado.

Plaza Towers Elementary School

Plaza Towers, having been rebuilt after the 2013 EF5, was again directly hit. Its new reinforced concrete construction held up better than the original facility, though the outer walls, windows, and roof were heavily damaged. Debris was scattered across its grounds. Officials later stated that the upgrades likely prevented a repeat of the 2013 tragedy.

Other regions

Beyond Moore, parts of South Oklahoma City and unincorporated Cleveland County sustained EF2 to EF3 damage. Scattered power outages extended into Norman and Midwest City. Rural homes along the western edge of the tornado’s path experienced EF3 damage to barns, vehicles, and tree lines.

Casualties

The death toll rose to at least 35, with more than 315 injuries reported. Several people were killed in vehicles, others in mobile homes or poorly anchored shelters. Recovery of victims was hampered by debris, flooding from burst pipes, and blocked roads. Identification and confirmation of casualties took nearly three weeks due to the scale of destruction.

Aftermath

Initial aid

Within hours, search-and-rescue teams were deployed from across Oklahoma and neighboring states. The Oklahoma National Guard and FEMA led recovery and coordination efforts. Over 30 temporary shelters were activated, and over 3,000 individuals were displaced. Food banks, mobile kitchens, and Red Cross units provided essential services. Emergency crews cleared key corridors first to allow for medical transport and power restoration.

Television changes and documentary specials

Several local stations suspended normal programming to provide wall-to-wall coverage for days. A series of memorial specials and survivor interviews aired nationally in the following weeks. Documentary crews from PBS and The Weather Channel embedded with Moore responders to produce retrospective specials highlighting resilience, engineering, and recovery.

See also

Tornado outbreak of May 11-12, 2030

1999 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado

Part of

The 2030 Moore tornado was the most destructive tornado in a two-day outbreak that produced 19 confirmed tornadoes across Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. Alongside the Moore tornado, the outbreak included the 2030 El Reno EF4 tornado and several EF2–EF3 events. The moderate-risk forecast verified with multiple cyclic supercells and high-end thermodynamic profiles contributing to violent tornado development across the Southern Plains. The outbreak reaffirmed central Oklahoma’s unfortunate status as one of the most tornado-prone regions in the world.