2030 Moore tornado: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The '''2030 Moore tornado''' was a catastrophic and violent [[Enhanced Fujita scale|EF5 tornado]] that struck the city of [[Wikipedia:Moore, Oklahoma|Moore, Oklahoma]] on May 11, 2030. As part of a larger tornado outbreak affecting the Southern Plains, this tornado caused widespread devastation across Cleveland and Oklahoma counties, leaving a trail of destruction reminiscent of the deadly tornadoes that struck the region in 1999 and 2013. The tornado reached a peak intensity of EF5 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, with estimated winds of 205 mph (330 km/h), and carved a destructive path through densely populated areas, making it one of the most intense tornadoes to impact the United States in recent history. | The '''2030 Moore tornado''' was a catastrophic and violent [[Enhanced Fujita scale|EF5 tornado]] that struck the city of [[Wikipedia:Moore, Oklahoma|Moore, Oklahoma]] on May 11, 2030. As part of a larger tornado outbreak affecting the Southern Plains, this tornado caused widespread devastation across Cleveland and Oklahoma counties, leaving a trail of destruction reminiscent of the deadly tornadoes that struck the region in 1999 and 2013. The tornado reached a peak intensity of EF5 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, with estimated winds of 205 mph (330 km/h), and carved a destructive path through densely populated areas, making it one of the most intense tornadoes to impact the United States in recent history. | ||

This was the third EF5 tornado to strike the city of Moore, following the devastating events of May 3, 1999, and May 20, 2013. It also marked the third EF5 tornado to occur in the United States since 2013, breaking a nearly two-decade lull in top-rated tornadoes. Despite the widespread damage throughout the city, the National Weather Service assigned the EF5 rating based on a single damage indicator: the complete destruction of a well-constructed restaurant in southern Moore. The rest of the tornado’s damage, while extreme, did not meet the | This was the third EF5 tornado to strike the city of Moore, following the devastating events of May 3, 1999, and May 20, 2013. It also marked the third EF5 tornado to occur in the United States since 2013, breaking a nearly two-decade lull in top-rated tornadoes. Despite the widespread damage throughout the city, the National Weather Service assigned the EF5 rating based on a single damage indicator: the complete destruction of a well-constructed restaurant in southern Moore. The rest of the tornado’s damage, while extreme and consistent with EF4 intensity, did not meet the required damage indicators for an EF5 rating. However, the destruction of the restaurant, which had been bolted to its foundation and engineered to high standards, supported winds well over 200 mph. | ||

== Meteorological synopsis == | == Meteorological synopsis == | ||

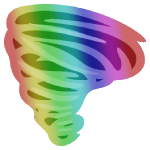

[[File:May112030SPCOutlook.png|thumb|left|1630 UTC Day 1 outlook on May 11.]] | [[File:May112030SPCOutlook.png|thumb|left|1630 UTC Day 1 outlook on May 11.]] | ||

On May 11, 2030, | On May 11, 2030, an intense upper-level trough began to eject into the central United States, interacting with rich low-level moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and a strengthening surface low across the Texas Panhandle. A sharpening dryline extended into western Oklahoma, while a warm front lifted northward through central Oklahoma. This set the stage for a volatile triple point scenario across the Oklahoma City metro. | ||

The Storm Prediction Center issued a Moderate Risk across Oklahoma, with a | Thermodynamic conditions were highly supportive of violent tornadoes. Temperatures reached 86 °F with dewpoints near 73 °F, and mixed-layer CAPE values soared to over 4450 J/kg. Lapse rates were steep, measured at 8.7 C/km in the 0–3 km layer and 7.4 C/km in the 3–6 km layer, supporting strong updraft acceleration. Shear was equally concerning, with 0–1 km storm-relative helicity reaching 457 m²/s² and effective bulk shear in excess of 45 knots. Precipitable water (PWAT) values, although somewhat modest at 0.4 inches, were sufficient to support supercellular convection with strong inflow. | ||

The Storm Prediction Center issued a Moderate Risk for severe weather across Oklahoma, with central Oklahoma placed under a Particularly Dangerous Situation (PDS) Tornado Watch during the early afternoon hours. The wording of the SPC discussion highlighted the risk of violent, long-track tornadoes. As the afternoon progressed, multiple discrete supercells formed along the dryline and quickly began producing tornadoes, culminating in the development of the deadly Moore EF5 tornado. | |||

== Tornado == | == Tornado == | ||

The 2030 Moore tornado touched down at | The 2030 Moore tornado first touched down at 1:21 p.m. CDT near the rural outskirts of Newcastle, Oklahoma. Within minutes, the tornado underwent rapid intensification as it moved northeast, crossing into the city of Moore. Radar imagery showed a strong and rapidly intensifying mesocyclone, along with a pronounced debris ball. The tornado began widening significantly as it approached the western edge of Moore, ultimately reaching a peak width of approximately 1 mile. | ||

The tornado’s path closely mirrored those of the 1999 and 2013 Moore tornadoes, further compounding the emotional toll on residents. As it passed through residential neighborhoods and commercial corridors, entire structures were leveled, and several homes were swept completely clean from their foundations. The most intense damage occurred in the southern part of the city, where a well-built and anchor-bolted restaurant was completely obliterated. Vehicles were thrown and mangled, some tossed over a quarter-mile. The tornado maintained peak intensity through central Moore before gradually weakening and dissipating around 2:13 p.m. west of Lake Stanley Draper. | |||

Despite | Despite widespread destruction, EF5 classification was supported by only one structure: the aforementioned restaurant. The National Weather Service determined that its complete removal, coupled with the structural integrity and anchoring, justified a 205 mph wind estimate. Other damage indicators in the tornado's path, while extremely severe, were insufficient on their own for EF5 status and were rated high-end EF4. | ||

== Impact == | == Impact == | ||

[[File:Moore2030Damage.jpg|thumb|right|EF5 damage to a well-built restaurant in Moore.]] | [[File:Moore2030Damage.jpg|thumb|right|EF5 damage to a well-built restaurant in Moore.]] | ||

The tornado's impact on Moore was nothing short of devastating. Over 2,000 homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed across a swath of residential neighborhoods, shopping centers, schools, and critical infrastructure. Streets were rendered impassable due to massive debris fields. Entire subdivisions were reduced to rubble, and widespread power outages blanketed much of Cleveland and Oklahoma counties. Communications systems were temporarily knocked offline in some areas. | |||

The tornado claimed at least 35 lives and injured more than 315 people. Several victims were killed inside homes that lacked basements or safe rooms, while others were caught in vehicles or businesses. Hospitals in Moore and Oklahoma City were overwhelmed with trauma cases, prompting emergency medical transports from surrounding counties. The financial toll was enormous, with damage estimates approaching $2.1 billion (2030 USD), ranking it among the most expensive tornadoes in U.S. history. | |||

In addition to the destruction of homes, two schools were either destroyed or sustained heavy damage. The Orr Family Farm, a well-known local landmark, was flattened along with adjacent equestrian facilities. Emergency responders, aided by volunteers and search dogs, worked through the night in dangerous conditions to search for survivors. Many residents credited timely warnings from local broadcasters and weather radios for saving lives, though the intensity and speed of the tornado still left little time to act. | |||

== Aftermath == | == Aftermath == | ||

The | Following the disaster, a federal emergency was declared, and extensive resources were mobilized. The Oklahoma National Guard established perimeter security and assisted with search and rescue, while FEMA coordinated the deployment of urban search teams, temporary housing units, and debris clearance. More than 30 shelters were opened across the metro, many housed in church gyms and school auditoriums. | ||

The tornado reignited national discussions about storm safety and construction standards. Moore, having already adopted stricter building codes after 2013, now faced questions about whether even those improved standards were sufficient. Engineers began studying the destroyed restaurant and other structural failures to inform future building designs in tornado-prone areas. | |||

Volunteers from | Volunteers poured in from around the country. Charitable organizations coordinated donations, food drives, and trauma counseling. Within weeks, city leaders began to outline long-term rebuilding plans, which emphasized storm shelter installations, enhanced community alert systems, and infrastructure reinforcement. The tragedy also prompted emergency management offices nationwide to revisit public outreach strategies for severe weather preparedness. | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 66: | Line 51: | ||

{{main|Tornado outbreak of May 11-12, 2030}} | {{main|Tornado outbreak of May 11-12, 2030}} | ||

The 2030 Moore tornado was the most destructive tornado in a two-day outbreak that produced 19 confirmed tornadoes across Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. Alongside the Moore tornado, the outbreak included the [[2030 El Reno tornado|2030 El Reno EF4 tornado]] and several EF2–EF3 events. The moderate-risk forecast verified with multiple cyclic supercells and high-end thermodynamic profiles contributing to violent tornado development across the Southern Plains. | The 2030 Moore tornado was the most destructive tornado in a two-day outbreak that produced 19 confirmed tornadoes across Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. Alongside the Moore tornado, the outbreak included the [[2030 El Reno tornado|2030 El Reno EF4 tornado]] and several EF2–EF3 events. The moderate-risk forecast verified with multiple cyclic supercells and high-end thermodynamic profiles contributing to violent tornado development across the Southern Plains. The outbreak reaffirmed central Oklahoma’s unfortunate status as one of the most tornado-prone regions in the world. | ||

Revision as of 20:32, 29 April 2025

The 2030 Moore tornado was a catastrophic and violent EF5 tornado that struck the city of Moore, Oklahoma on May 11, 2030. As part of a larger tornado outbreak affecting the Southern Plains, this tornado caused widespread devastation across Cleveland and Oklahoma counties, leaving a trail of destruction reminiscent of the deadly tornadoes that struck the region in 1999 and 2013. The tornado reached a peak intensity of EF5 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, with estimated winds of 205 mph (330 km/h), and carved a destructive path through densely populated areas, making it one of the most intense tornadoes to impact the United States in recent history.

This was the third EF5 tornado to strike the city of Moore, following the devastating events of May 3, 1999, and May 20, 2013. It also marked the third EF5 tornado to occur in the United States since 2013, breaking a nearly two-decade lull in top-rated tornadoes. Despite the widespread damage throughout the city, the National Weather Service assigned the EF5 rating based on a single damage indicator: the complete destruction of a well-constructed restaurant in southern Moore. The rest of the tornado’s damage, while extreme and consistent with EF4 intensity, did not meet the required damage indicators for an EF5 rating. However, the destruction of the restaurant, which had been bolted to its foundation and engineered to high standards, supported winds well over 200 mph.

Meteorological synopsis

On May 11, 2030, an intense upper-level trough began to eject into the central United States, interacting with rich low-level moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and a strengthening surface low across the Texas Panhandle. A sharpening dryline extended into western Oklahoma, while a warm front lifted northward through central Oklahoma. This set the stage for a volatile triple point scenario across the Oklahoma City metro.

Thermodynamic conditions were highly supportive of violent tornadoes. Temperatures reached 86 °F with dewpoints near 73 °F, and mixed-layer CAPE values soared to over 4450 J/kg. Lapse rates were steep, measured at 8.7 C/km in the 0–3 km layer and 7.4 C/km in the 3–6 km layer, supporting strong updraft acceleration. Shear was equally concerning, with 0–1 km storm-relative helicity reaching 457 m²/s² and effective bulk shear in excess of 45 knots. Precipitable water (PWAT) values, although somewhat modest at 0.4 inches, were sufficient to support supercellular convection with strong inflow.

The Storm Prediction Center issued a Moderate Risk for severe weather across Oklahoma, with central Oklahoma placed under a Particularly Dangerous Situation (PDS) Tornado Watch during the early afternoon hours. The wording of the SPC discussion highlighted the risk of violent, long-track tornadoes. As the afternoon progressed, multiple discrete supercells formed along the dryline and quickly began producing tornadoes, culminating in the development of the deadly Moore EF5 tornado.

Tornado

The 2030 Moore tornado first touched down at 1:21 p.m. CDT near the rural outskirts of Newcastle, Oklahoma. Within minutes, the tornado underwent rapid intensification as it moved northeast, crossing into the city of Moore. Radar imagery showed a strong and rapidly intensifying mesocyclone, along with a pronounced debris ball. The tornado began widening significantly as it approached the western edge of Moore, ultimately reaching a peak width of approximately 1 mile.

The tornado’s path closely mirrored those of the 1999 and 2013 Moore tornadoes, further compounding the emotional toll on residents. As it passed through residential neighborhoods and commercial corridors, entire structures were leveled, and several homes were swept completely clean from their foundations. The most intense damage occurred in the southern part of the city, where a well-built and anchor-bolted restaurant was completely obliterated. Vehicles were thrown and mangled, some tossed over a quarter-mile. The tornado maintained peak intensity through central Moore before gradually weakening and dissipating around 2:13 p.m. west of Lake Stanley Draper.

Despite widespread destruction, EF5 classification was supported by only one structure: the aforementioned restaurant. The National Weather Service determined that its complete removal, coupled with the structural integrity and anchoring, justified a 205 mph wind estimate. Other damage indicators in the tornado's path, while extremely severe, were insufficient on their own for EF5 status and were rated high-end EF4.

Impact

The tornado's impact on Moore was nothing short of devastating. Over 2,000 homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed across a swath of residential neighborhoods, shopping centers, schools, and critical infrastructure. Streets were rendered impassable due to massive debris fields. Entire subdivisions were reduced to rubble, and widespread power outages blanketed much of Cleveland and Oklahoma counties. Communications systems were temporarily knocked offline in some areas.

The tornado claimed at least 35 lives and injured more than 315 people. Several victims were killed inside homes that lacked basements or safe rooms, while others were caught in vehicles or businesses. Hospitals in Moore and Oklahoma City were overwhelmed with trauma cases, prompting emergency medical transports from surrounding counties. The financial toll was enormous, with damage estimates approaching $2.1 billion (2030 USD), ranking it among the most expensive tornadoes in U.S. history.

In addition to the destruction of homes, two schools were either destroyed or sustained heavy damage. The Orr Family Farm, a well-known local landmark, was flattened along with adjacent equestrian facilities. Emergency responders, aided by volunteers and search dogs, worked through the night in dangerous conditions to search for survivors. Many residents credited timely warnings from local broadcasters and weather radios for saving lives, though the intensity and speed of the tornado still left little time to act.

Aftermath

Following the disaster, a federal emergency was declared, and extensive resources were mobilized. The Oklahoma National Guard established perimeter security and assisted with search and rescue, while FEMA coordinated the deployment of urban search teams, temporary housing units, and debris clearance. More than 30 shelters were opened across the metro, many housed in church gyms and school auditoriums.

The tornado reignited national discussions about storm safety and construction standards. Moore, having already adopted stricter building codes after 2013, now faced questions about whether even those improved standards were sufficient. Engineers began studying the destroyed restaurant and other structural failures to inform future building designs in tornado-prone areas.

Volunteers poured in from around the country. Charitable organizations coordinated donations, food drives, and trauma counseling. Within weeks, city leaders began to outline long-term rebuilding plans, which emphasized storm shelter installations, enhanced community alert systems, and infrastructure reinforcement. The tragedy also prompted emergency management offices nationwide to revisit public outreach strategies for severe weather preparedness.

See also

Tornado outbreak of May 11-12, 2030

1999 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado

Part of

The 2030 Moore tornado was the most destructive tornado in a two-day outbreak that produced 19 confirmed tornadoes across Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. Alongside the Moore tornado, the outbreak included the 2030 El Reno EF4 tornado and several EF2–EF3 events. The moderate-risk forecast verified with multiple cyclic supercells and high-end thermodynamic profiles contributing to violent tornado development across the Southern Plains. The outbreak reaffirmed central Oklahoma’s unfortunate status as one of the most tornado-prone regions in the world.